The concept literally no one likes rolls around every year. We’re stuck with the fiscal space forever. The reason for the hated concept’s longevity is simple: the fiscal space is a part of our system of laws now. President Michael D Higgins signed the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union into law in 2012 after 60 per cent of us voted to introduce it into the Irish Constitution.

Love or hate the fiscal space, figuring out what the space is and arguing over how to apportion it are now a part of the budgetary calculus of the Irish state.

The fiscal space is the money available to a government to use over and above what it is spending already, conditional on the budgetary rules enshrined in law being adhered to, and a set of assumptions about the economy’s future turning out to be true.

The basic idea of rules-based fiscal legislation is to achieve a sustainable national debt. The thinking behind this is simple: if your debt levels are fairly low as a country, when a crisis comes along, you’ll have the ability to borrow to fight the crisis. This macro objective is implemented as a numerical ceiling on borrowing and the use of borrowed resources for public current and capital investment. The rules constrain what any finance minister might want to do, and forces a longer and more drawn-out budgetary process.

There should never again be a moment like we had in 2004 when then finance minister Charlie McCreevy announced decentralisation to the surprise of many in his own government, let alone the parliament tasked with approving the decision to pay for it. The idea of decentralisation was to move 10,300 civil and public servants from Dublin to 53 locations in 25 counties. Decentralisation was a bad idea that failed in its objectives, not to mention an expensive one. The policy was finally killed off in 2012, with only around 3,400 civil and public servants relocated.

If the rules limit stupid ‘if I have it, I spend it’ policies, they also limit one-off spending initiatives and curtail crucial capital investment. So if, say, somewhere between €13 billion and €19 billion landed into the government’s coffers from a very large company associated with fruit, the government would not have total discretion over where to spend it. In previous eras, the government would have had much more discretion. Again, we voted to remove this discretion, probably thanks to seeing ‘if I have it I spend it’ in action repeatedly bankrupt the state.

There are three issues to consider. First, just what is the number? Second, how should it be distributed between tax decreases and spending increases? Third, can we believe the number?

What is the number?

To figure out the fiscal space, you project how much your economy will be able to produce over a period of time, say 2017 to 2021. This is called a ‘supply side’ estimate, and this estimate is highly technical and highly contentious politically. More on that in a minute. You stick this estimate into a model of the Irish economy, assume it grows by some amount, and then make allowances for demographics, the public capital programme and public sector pay increases.

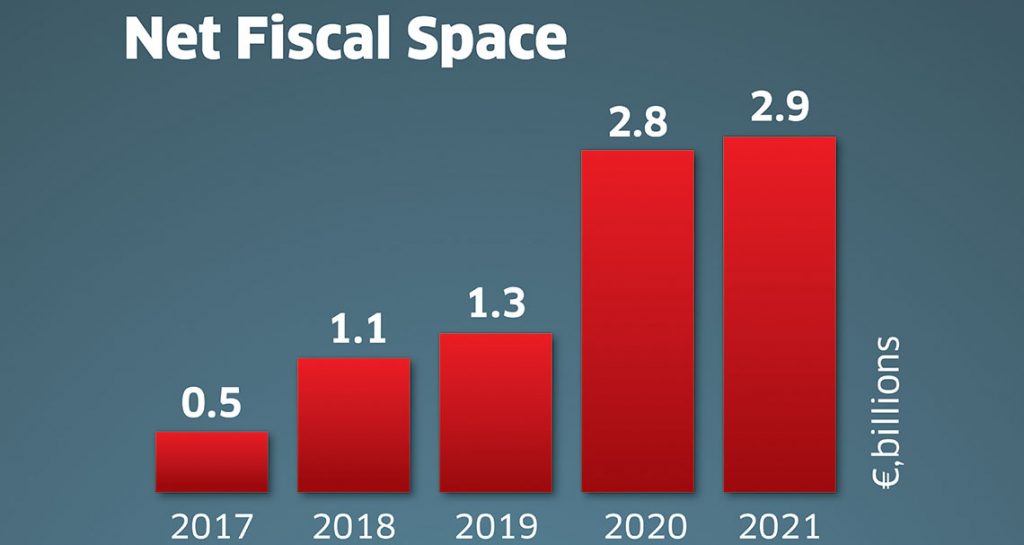

The Department of Finance estimates the net fiscal space is about €8.6 billion from 2017 to 2021. That is the amount of money to be played with. The graph shows the amount in billions of euro to be spent each year.

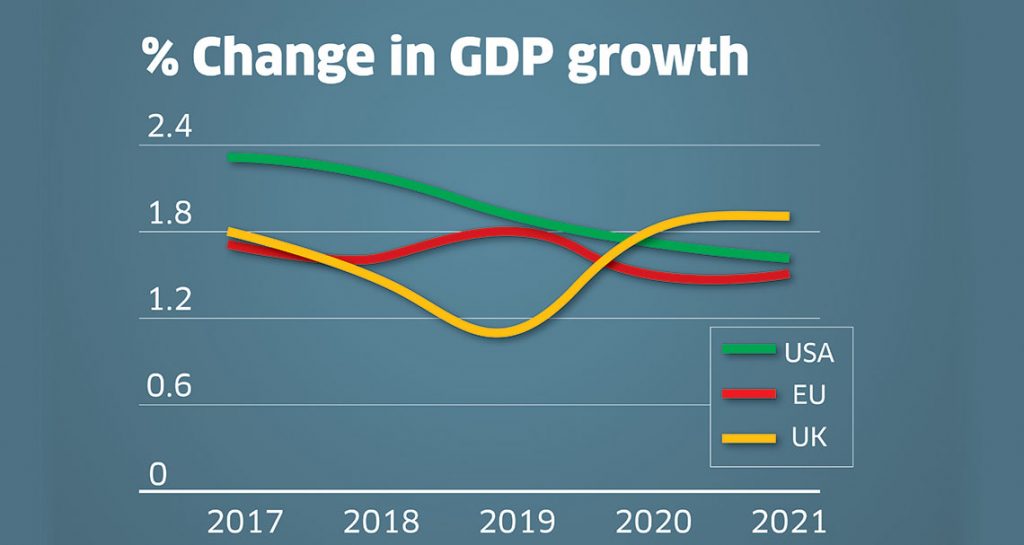

A few caveats are worth putting in here. The amount of taxes the government is taking in is slightly below where it was expected to be in the first quarter of this year. That’s not a deal breaker as a large chunk of taxation revenue comes in towards the end of the year, but another quarter off the mark would certainly diminish the available fiscal space. A tiny open economy like Ireland is vulnerable to changes in the fortunes of our major trading partners. The graph shows how the Department of Finance views these economies growth prospects between 2017 and 2021. There’s a sharp Brexit-shaped shock for Britain, but it bounces back pretty quickly. The US declines somewhat, while the EU weathers the Brexit storm somewhat better than Britain. Obviously a large change in the euro/sterling exchange rate would wipe out the margins of companies that trade with Britain, and a spike in the price of oil or gas would also affect the cost structure of the economy negatively.

To move forward, you have to plan, and plan prudently. If these assumptions turn out to be wrong, overly optimistic or overly pessimistic, then we might be in trouble with our fiscal space recommendation.

For 2018, the fiscal space is pretty small, at around €1.1 billion to €1.2 billion. For a sense of scale, the Irish government will spend over €70 billion in 2017. Despite already figuring in demographic and public sector pay, a lot of this €1.2 billion could already be taken up with other pre-announced spending on health, a tax carryover and a refund of at least some of the €0.12 billion paid in water charges, plus whatever it costs to run Irish Water sans water charges (say €0.2 billion) and capital spending on roads, hospitals, and schools. Last week, Minister for Finance Michael Noonan reckoned the amount of cash the government would have to play with would be around €550 million or so. As in 2016, money will be found in what Noonan called ‘chunky’ spending areas at the last minute - sometimes the morning of the budget - but in general planning on apportioning €550 million will be the order of the day.

The Irish Fiscal Advisory Council thinks there’s less fiscal space than €8.6 billion because many spending programmes will be indexed to inflation as well, so the pension bill, the social welfare bill, the carer’s allowance bill and so forth will grow a bit and eat into this envelope.

This government shouldn’t be remembered for new politics, it should be remembered as the Building Government

The Programme for Partnership Government doesn’t cover the period from 2017 to 2021. It covers three budgets, and so takes us up to 2019. The agreement within this document is to achieve at least a 2:1 split between public spending and tax reductions.

Assuming this holds (we’re all about the assumptions in this column), that implies about €1.6 billion spent on increasing public services between 2018 and 2019, and €0.8 billion being spent on tax decreases.

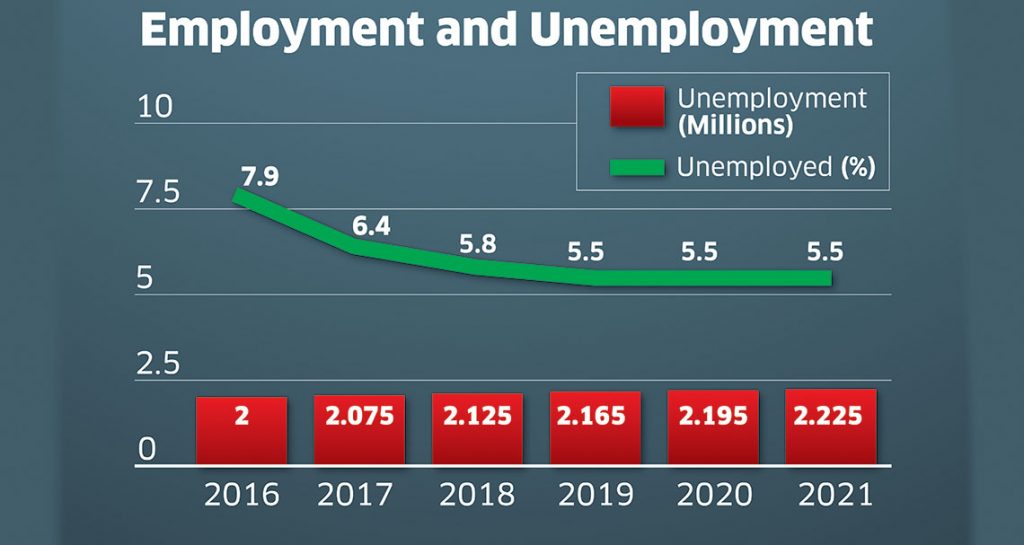

This is probably a mistake. We have over two million people in work now, and there are 2.225 million people forecast to be working in the economy by 2021. The unemployment rate is forecast to fall from 7.9 per cent in 2016 to 5.5 per cent in 2021, with inflation due to increase to around 2 per cent in 2021 as well. That looks a lot like an economy at full employment.

Given that this is the glide path of the economy for the next few years, now is not the time to spend more money on salaries for lecturers and tax breaks for developers. Now is not the time to decrease income taxes that much, either - there’s a fair bit of inflation built into the system as a result of a pretty tight labour market.

Despite being loved as a political talking point, I don’t think the issue of labour productivity is tied up too much with taxation. I haven’t seen much evidence of this in the Irish context. I have seen lots and lots and lots of reports arguing that Ireland’s deficit in capital spending is chronic, and reaching crisis levels across many areas of the economy. The spending priorities of the government based on its own forecasts should be: 1. Capital spending on housing. 2. Capital spending on hospitals and primary care centres. 3. Capital spending on schools. 4. Capital spending on roads. 5. Current spending on services. 6. Tax decreases for lower income households. The 2:1 spending ratio should be scrapped. This government should be remembered not as the first vessel of new politics. It should be remembered as the Building Government.

There is no sense that public sector workers need more money. As evidence for this, notice the number of people leaving the public sector for better work in the private sector. It’s not even a trickle, never mind a flood. There is a great sense that services are not adequately supplied and organised and service provision could be extended.

Can we believe the number?

Ireland is having a hard time with official statistics at the moment. Between dodgy housing numbers, gardaí breathalysing themselves and making up test results and leprechauns in our national accounts, an air of mistrust pervades much of the discussions we have today. The fiscal space is a number every party bar Sinn Féin got wrong before the last election. The Fiscal Council’s assessment of the space is (and probably will always be) the most conservative, but it includes things like indexation which the government of the day might choose not to do. The key issue is how we estimate the fiscal space. The fiscal space relies on getting a figure for what is called the structural budget balances, the difference between government spending and the money a government makes in taxation, corrected for the impact of the economic cycle and some other temporary measures.

The estimation is produced using a commonly agreed methodology for all EU states. This treats Germany as if it was Ireland and Ireland as if it was Germany. This is a big mistake. Ireland is a tiny open economy subject to many external shocks, and with a particular industrial structure. Remember our fruit-related friends? Treating us the same as Germany in how our economy might evolve is a mistake.

The Department of Finance is coming up with a new way to measure how much stuff the economy can produce - its supply side - and hopefully this will be acceptable to Brussels. If they get the computation of the fiscal space more accurately typed to the Irish economy, it might have the effect of loosening the fiscal rules in practice. Watch this space. This is the kind of unglamorous, wonky work that in the end might do the state some real service.

Similarly, the fiscal rules are considered as ‘medium term’ objectives, on the order of roughly five to seven years. Capital expenditure on infrastructure projects like extending the M20 motorway from Limerick to Cork, or the Dublin Metro, or new maternity hospitals, typically have a much longer term structure, say 20 to 50 years. When it comes to capital spending, you pay a large cost to build the thing, but derive benefits for decades to come. This is very difficult to square with the fiscal rules which span a fraction of the time.

So here comes the fiscal space again. It’s here to stay. We can bend how it is computed a bit, we can change how we spend the extra money a growing economy produces, but we can’t mitigate the external risks to the economy, or stop people wanting to spend more on the things they care about most. We need to use the fiscal space for capital expenditure first and foremost. Think bridges and hospitals, not salaries for engineers and doctors, and we’ll be fine.