The government and our civil service have played a blinder since before the Brexit vote. As the referendum was announced, a working group was set up within the Department of the Taoiseach to consider the likely impacts of a Leave vote on Ireland and the nation’s best response.

The day after the Brexit vote, as Britain’s political class sat paralysed in shock, waiting for Bank of England governor Mark Carney to save them, Enda Kenny appeared to the press with a very large and detailed list of priorities by government department.

Kenny’s performance wasn’t statesman-like: he was a statesman that day. The contrast between our two islands was almost jarring. Britain had no plan, but we had.

In the weeks following the Brexit vote, the EU laid out its negotiating priorities, and has stuck to them since. Only one element has changed: Ireland is now front and centre. President of the EU council Donald Tusk said last week: “It is clear that progress on people, money and Ireland must come first.”

The government, and its diplomatic arm in particular, has love-bombed the capitals of Europe, making the case for Ireland. It succeeded brilliantly in the formal inclusion of the ‘Kenny text’ into the EU’s negotiating parameters, agreed by the heads of state at a recent summit.

It’s worth repeating the Kenny text in full.

“The European Council acknowledges that the Good Friday Agreement expressly provides for an agreed mechanism whereby a united Ireland may be brought about through peaceful and democratic means. In this regard, the European Council acknowledges that, in accordance with international law, the entire territory of such a united Ireland would thus be part of the European Union.”

The Kenny text provides for a means to ensure the Good Friday Agreement isn’t undermined by any negotiation, and for a way to negotiate clearly on the border arrangements between the Republic and the North.

Yes, it’s only a start, but it’s the best possible start.

A win for Kenny of historical significance

It is important to note the historic significance of the Article 50 negotiations and to place them in their correct context. The kingdoms of Ireland and Great Britain were united in 1801 by acts of the Irish and British parliaments.

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty marked the beginning of the Irish secession, which is in many ways analogous to today’s Article 50 process, but with much less complexity. Westminster passed the Irish Free State Constitution Act in 1922.

That act provided for a common travel area between Britain, Ireland, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man. The starting point of any negotiation in 2017 and 2018 is to hew as closely as possible to the 1922 arrangement, which underpins a common labour market.

Given the range of forces allied against it, the government did an amazing job, pushing the need for 26 other states with their own diverse (and insular) needs to think about Ireland as hard as they could. Recently in this column I was deeply sceptical of its ability to do this, given the competing claims and individual national interests at play. I was wrong to be so cynical. The government, and Enda Kenny, prevailed.

In a stream of nearly relentless criticism of the government, we have to acknowledge the good work done here. There was no pre-ordained outcome: it was not inevitable that Europe would care at all about Ireland. The government did its job, and did it well. I know unalloyed praise for the government sometimes feels like listening to cats barking, but there shouldn’t be an asymmetry between how we view the successes and failures of any government.

One part of the problem is that when the government succeeds, it typically does so quietly. Really good public policy is like really good plumbing, or software: it just works. We only notice either when they seize up.

It is amazing how politics moves. Had he left office in February, Enda Kenny would be remembered for his catastrophic mishandling of the Sergeant Maurice McCabe affair. Just two months later, as he prepares to leave office following the Kenny text, he has the successful parameters for the Brexit negotiation to bookend a remarkable political career. It doesn’t erase the failures of the past, of course, but history will judge him differently as a result of the Kenny text.

Context matters. The state will endure beyond any of us, and beyond any individual taoiseach. Whoever holds that high office has to consider fiscal matters above almost every other issue.

The state expects to lose up to 3 per cent of GDP over ten years as a result of Brexit, and this might cost Ireland 40,000 jobs, mostly in indigenous sectors. For a sense of scale, there are about 400,000 jobs directly dependent on the trading relationship Ireland has with Britain.

The British people are convulsed by a post-imperial fantasy sold to them by right-wing newspapers. The Article 50 negotiations are going to be very hard for them as this fantasy is dispelled. The Irish are their greatest allies within the EU-26 negotiating team, because our incentives now align perfectly with theirs. The softer the Brexit, the better it is for Ireland.

Brexit is expected to have a negative impact on Ireland’s balance of payments - the difference between what it sells to the world, and what it buys from the world.

I’ve mentioned in this column many times that Ireland’s largest export by value is, in fact, pharmaceuticals, and Belgium is our largest trading partner as a result. Agriculture is a huge sector in Ireland by value, and it employs about 170,000 people. These people produce almost one-fifth of the beef used by McDonald’s in Europe. They produce about one tenth of all the baby formula consumed in the world. All from a country with a population the size of Manchester. For many of them, Brexit represents a massive challenge to their livelihoods.

Budget 2018 must be framed as the Brexit budget which will react to protect the interests of those most affected by the now likely hard Brexit. But for a Brexit budget, you need fiscal space. And that seems to be disappearing.

A fiscal puzzle - and the answer isn’t jobs

You don’t try to figure out what’s going on in an economy by using one measure. Firstly, most economic data is rubbish by scientific standards, and usually collected for some other purpose. Secondly, the figures are usually for one sector or one industry, or survey-based and sometimes biased.

Despite their deficiencies, however, they measure the same complex system, so typically they move together. When we see industrial production increasing by 2.6 per cent in March 2017, and the Live Register total decreasing by 4,600 for a 6.2 per cent unemployment rate in April 2017, when we see Vat receipts up by €602 million or 14.5 per cent in annual terms, we can speculate that more people are working, and they are buying more things. We should therefore expect to see more taxes being paid from income.

Here’s the puzzle: income taxes increased by only €14 million to €1.7 billion in April, and this increase is below target, the second such miss this year. Excise and corporation taxes are down also, but these are not ‘smooth’ taxes such as income and so we shouldn’t take a miss too seriously.

What we should focus on are the income tax receipts. More people in work should, all things being equal, correspond to more people paying income taxes. But it hasn’t.

Three explanations are likely.

First, it could be that many of the new jobs created are low-paid and so don’t attract a significant amount of income tax.

This is a bad thing for many reasons, and Brexit is one of them. Low-paid jobs are bad for social mobility, family formation and social cohesion, and they are obviously not great when it comes to income taxes.

Low-paid jobs are typically low-productivity jobs. They are the first to go if there is any shock to the business, such as the one we know Brexit will create. Ireland desperately needs an increase in productivity.

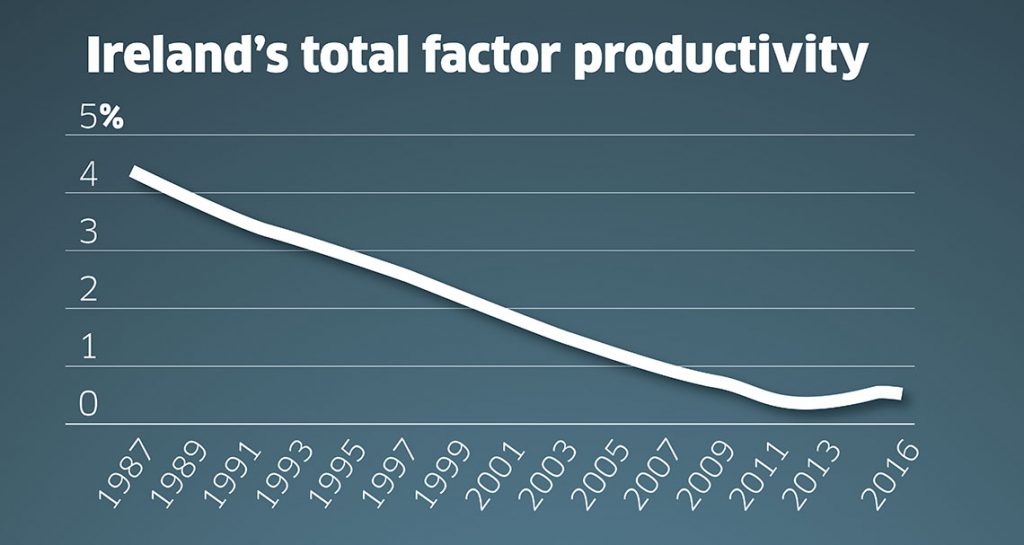

The chart shows one measure of productivity growth called ‘total factor productivity’. In 1987, Ireland’s total factor productivity grew by 4.5 per cent. In 2016, it grew by 0.55 per cent. In the long run, you don’t get growth without increases in productivity.

Second, it could be that many of the new jobs don’t have enough hours associated with them, or that they are just taxed in a different way, that is, using PRSI and PAYE rather than USC.

The number of average weekly paid hours has increased from 31.8 hours in 2009 to 32.1 hours in 2016, and average total labour costs are up. The composition of these hours worked and the wages paid might have changed post-crisis, but we don’t have evidence of that yet.

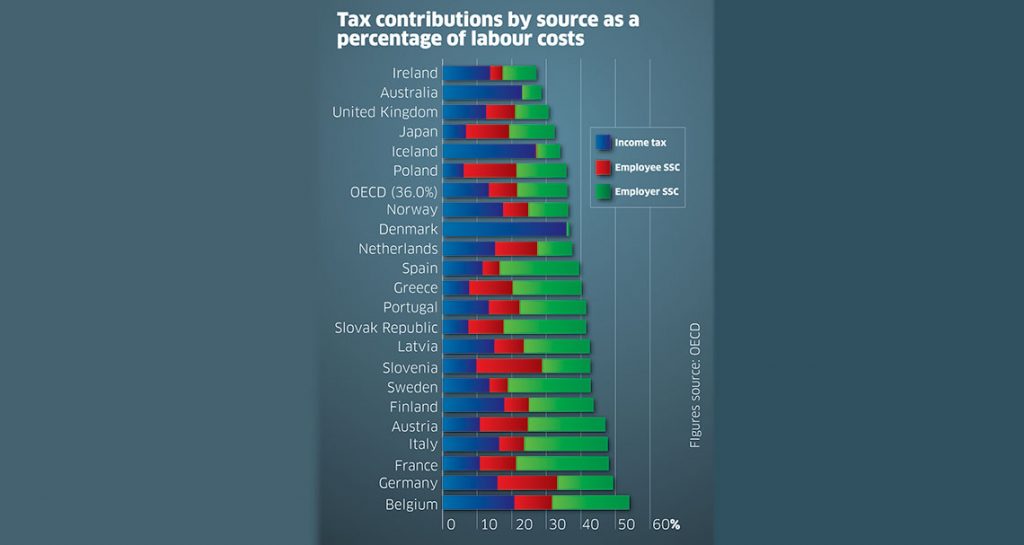

Third, it is possible that the nature of our tax system has changed. The tax wedge is a measure of the tax on labour income, which includes the tax paid by both the employee and the employer. Of 35 OECD member countries in 2016, Ireland had the 29th lowest tax wedge. The average single worker in Ireland faces a tax wedge of 27 per cent in 2016 compared with the OECD average of 36.0 per cent. The tax wedge has risen from 22 per cent in 2008 to 27 per cent in 2016.

Ireland is not a high-tax country for many of its workers, despite what many believe. The table shows how much workers and corporations pay towards their social security contributions as a percentage of labour costs. Ireland is bottom of the list.

The structure of our tax system is why calls to pay for everything from ‘general taxation’ won’t all work: not enough of us pay enough into the pool of taxable funds to resource things such as hospitals, schools and roads.

You can achieve a single-payer system for most social services if households, firms and the import/export sector are taxed at a fairly high rate, but we all know that won’t fly.

Brexit will take more jobs away in trade displacement and uncertainty than it gives in foreign direct investment. Our tax system will probably not be able to deliver enough funds to guard against the worst effects of Brexit. Our government has shown it can get the job done when it comes to Brexit. The next key test will be Budget 2018.