Some of the world’s first public sector workers were donkeys. This fact is not well known, and it takes some explaining. Bear with me a moment.

In 1696, the great mathematician Sir Isaac Newton retired from scientific work and took up a sinecure as warden, and later master, of the Royal Mint.

The word ‘sinecure’ literally means ‘without a care’. The wardenship of the mint was a do-nothing job for a man who had achieved more than most by the time he was 55. Newton had, among many other things, invented the calculus. He was both the first scientist and the last magician.

Thanks to Newton, humanity now knew why there were tides, could predict the movement of planets, and understood the nature of light, heat and motion. He delved deeply into alchemy and into spirituality at the same time. Not bad, as lives go.

So Newton, his scientific work well behind him, got a nice job looking after the currency of the empire. At the time coins were made of gold and silver, which were clipped and destroyed regularly, thus reducing their value. His knowledge of chemistry and metallurgy helped him redesign the manner in which coins are made.

Newton changed the chemical composition of the coins and added specially grooved edges so it would be obvious if they had been clipped. Take out a coin from your pocket and look at the edges. They have grooves in them in part because of the tradition begun by Newton. He also changed how the coins were ‘struck’, imprinted with the face of the king, the date and so on.

Coins used to be struck by hand, using big hammers. Newton invented coin presses powered by - you guessed it - donkeys. His coins were of impeccable quality and were far less likely to be clipped or counterfeited. Anyone interested in this time in Newton’s life should read JH Craig’s Newton at the Mint. It’s a small book, but well worth your time.

It seems incredible now, but the mint in the 17th century was mostly crewed by people who did not have permanent jobs or even long association with it. The incentives to do a bad job and to be corrupt were manifold.

Newton changed that, prosecuting wrongdoing, bringing higher levels of training into the mint by creating security of tenure in exchange for having a permanent position, both for donkeys and their keepers. In that way, he helped create the foundations of a civil service.

In Newton’s mint you have the three main elements you still see today: a deep and lasting vocational connection to the workings of the state, a guarantee of work into the future, an expectation of higher training. And a few donkeys.

✽ ✽ ✽

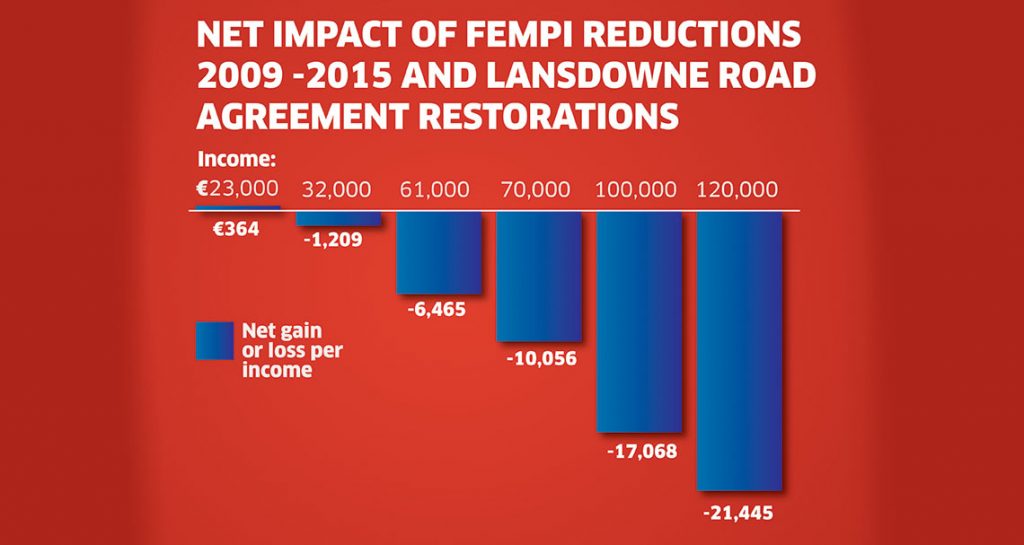

On the individual level, a public sector worker on €32,000 lost some €1,200 between the cuts and the restorations, while a public sector worker on €100,000 lost about €17,000.

Post-emergency pension drama

That emergency has passed - for the state, if not for all its citizens - but many of the pay reductions remain, especially for those public sector workers on about €40,000 or more. Those on lower pay scales have seen their cuts largely reversed. The question for the minister and his officials is: how quickly will pay be restored, and in exchange for which productivity changes to which elements of the service?

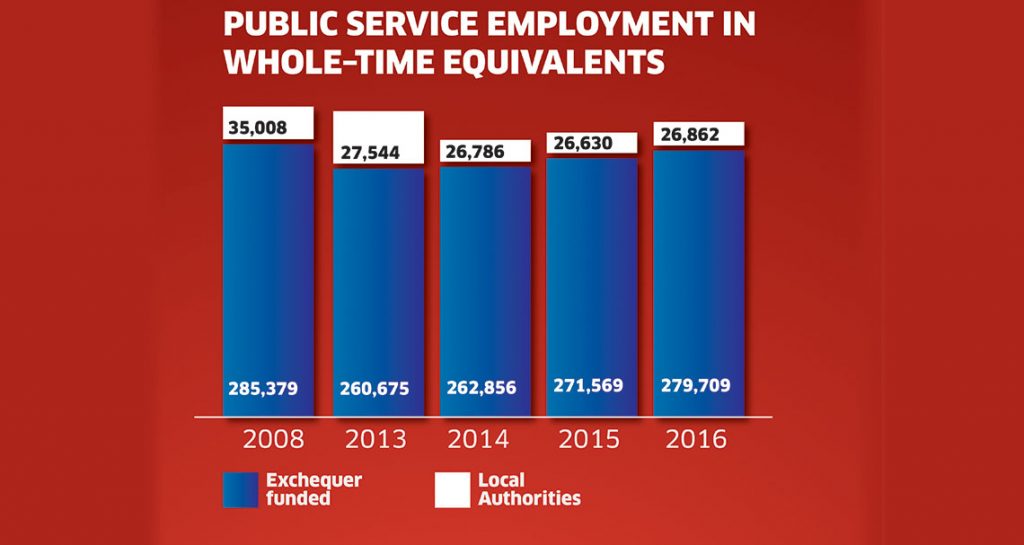

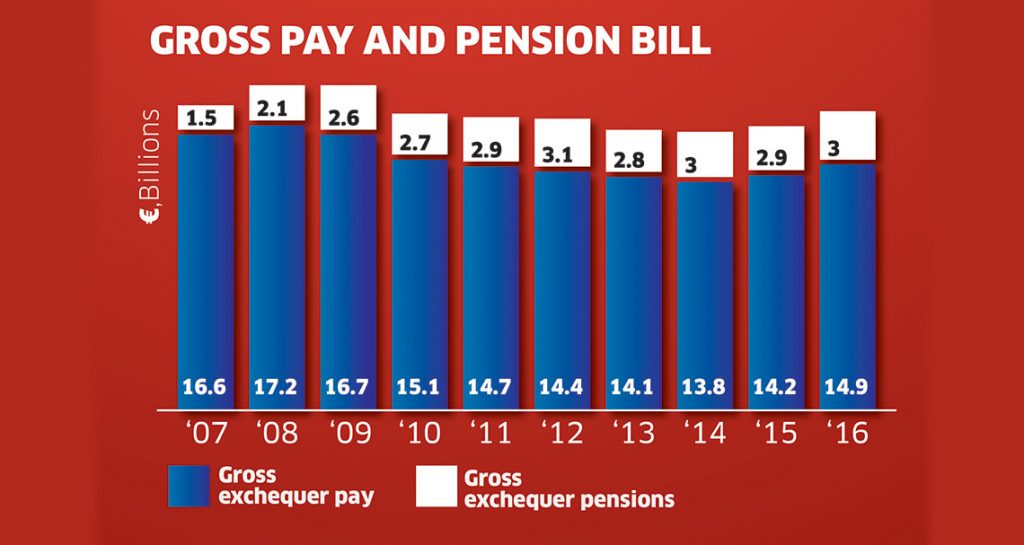

People will remember that in 2008 we had about 320,000 public sector workers. There are about 306,000 today. The gross pay bill for these workers, including the pensions of all of the retired workers, who are paid from current taxation and not a specific pension pot, was €18.1 billion in 2007, and is €17.9 billion today. The net figure is far lower when you consider how much tax those earning over €40,000 pay back to the government, but this is harder to calculate. The pension costs have risen, as many in 2009 and 2010 chose to retire on larger pensions.

Demographic changes alone mean that pension servicing costs will rise. The old age dependency ratio is the ratio of those over 75 to those between 25 and 69. In 1975 this ratio was 13. By 2050 it will be 21.

There are only three solutions to containing the cost explosion in public sector pensions: reduce the expenditure by reducing the pension amount, grow the economy more rapidly than the pensions grow, or isolate and study the old so it can be determined what nutrients they have that might be extracted for our personal use.

Killing and eating the old, as Homer Simpson suggested, doesn’t seem like a runner politically (or at least not in the era of minority government). The long run growth rate of a highly developed economy like Ireland’s is between 2 and 3 per cent per year. The pension bill will certainly grow faster than that by 2025, let alone 2050.

In its submission to the commission, the Department of Public Expenditure itself estimated the differential in employer contribution between a private sector pension and a pre-2013 public sector pension on average at +18 per cent, and in some cases +46 per cent for hospital consultants. The post-2013 scheme is much closer to a private sector model and carries a +2 per cent difference on average.

Consider the following thought experiment: allow private sector workers to enrol in the pre-2013 public sector pension scheme and let them pay the going rate. There would be a deluge of people willing to do so for a defined benefit scheme where the provider is very unlikely to go broke (that said, we’ve done it three times since independence).

The resulting influx might well change how those on low to middle incomes save for their pension, but it would make funding other services like hospitals and roads much more difficult. This would probably also be true for the post-2013 scheme - people are living longer and those on defined benefit schemes have a much better chance of living well into their retirement than if they are on low and middle incomes. Obviously those on higher incomes are probably better off in the private sector, as the salaries they can earn there are far higher than in the public sector.

It’s not pay, it’s not pensions, it’s tenure

The commission did a great job outlining the evidence base for the negotiations to come. They are also publishing all of their workings and assumptions, which as a measure of transparency in policymaking is brilliant.

The one area they did not examine is the benefit of long-term permanency and security of tenure.

Some public sector workers are still effectively unfireable, and their status insulates them against movements in the business cycle, which is a massive benefit in terms of being able to save less, apply for credit more easily, and plan at longer time spans. This benefit was not priced by the commission.

In terms of organisational change, it also slows things down. Workers with security of tenure who perform well are not a problem, of course: they will continue to be assets to the state. However, workers who are not performing well also stay within the system, which calcifies it to a certain extent.

Consider another thought experiment. How much money would you have to offer a public sector worker to remove their tenure? That is, to move them to a contract where, subject to the needs of the organisation, that worker can be let go like a private sector worker? Here you would have to add up all the years of foregone wages, discounted appropriately, and get a sense of how likely someone is to be let go.

To take an example, I’m 38, and I expect to work another 30 years. The cost for me would be enormous, and this is an unpriced benefit every public sector worker enjoys that isn’t yet well understood by the commission.

The first key here to understanding the difference in public sector pay, terms, and conditions is that they are all paid for by the private sector. Private sector workers fund the whole thing, and they have a right to be enraged when a public sector worker, just by dint of a job choice, enjoys a stream of lifetime benefits they do not. The commission has made most of these benefits clear, and has clearly been at pains to be as fair to every element of the system as it could reasonably be, which is not an easy job.

The second key to understanding is this: the wages of the public sector are spent on the goods and services the private sector sells. One sector’s income is another’s expenditure. Cutting one entails cuts to the other. So balance is everything and will be vital in the forthcoming negotiations.

Decent wages, terms and conditions for all

We are one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Workers should enjoy wages commensurate with their productivity and skill levels, and generous terms and conditions. They should look forward to long retirements paid for by their work and by their employers. This should be true regardless of whether they work in the private sector or the public sector. James Connolly in the early 20th century had it right: the cause of labour is the cause of Ireland. The real discussion should be why so many in the private sector have no pensions, and no relative security of tenure.

Newton had it right too in the late 17th century: those in service of the state should be well trained, and well paid.

In the 21st century I want an Ireland of educated people who do remarkable things with their hands and their minds, and are rewarded for doing so, when they are young and when they are old.

The closer we get to removing the general exasperation the public has with public sector workers, some of which is based on poor data and misinformation, the closer we are to figuring out what kind of Ireland allows everyone to prosper.